Ask Me About My Lobotomy! The Illusion of Cure

- R.D. Ordovich-Clarkson

- Jan 13

- 6 min read

By Dr. O. Clarkson

The era of the lobotomy marks one of the most disturbing chapters in modern medical history, not only because of its cruelty, but also because it emerged from a sense of sheer scientific hubris. For a brief yet troubling period, the deliberate destruction of brain tissue was celebrated as a therapeutic breakthrough. It was a solution to some of the most complex psychological conditions known to medicine, particularly psychosis, and eventually extended to the control of 'unruly' women. In retrospect, the lobotomy forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: medicine is most dangerous when evidence is ignored and when treatments are unquestioned—facts that we still contend with to this day.

At the center of this history lies the frontal lobe, a region of the brain uniquely responsible for many of the traits we associate with being human. Executive function, emotional regulation, impulse control, moral reasoning, future planning, personality, and the capacity for imagination all converge here. Compared with most animals, it is the expanded and highly integrated frontal cortex that allows humans to inhibit instinct, reflect on meaning, and construct coherent inner lives. To intervene surgically in this region is not merely to treat symptoms, but to alter identity itself.

The Birth of a Medical Panacea

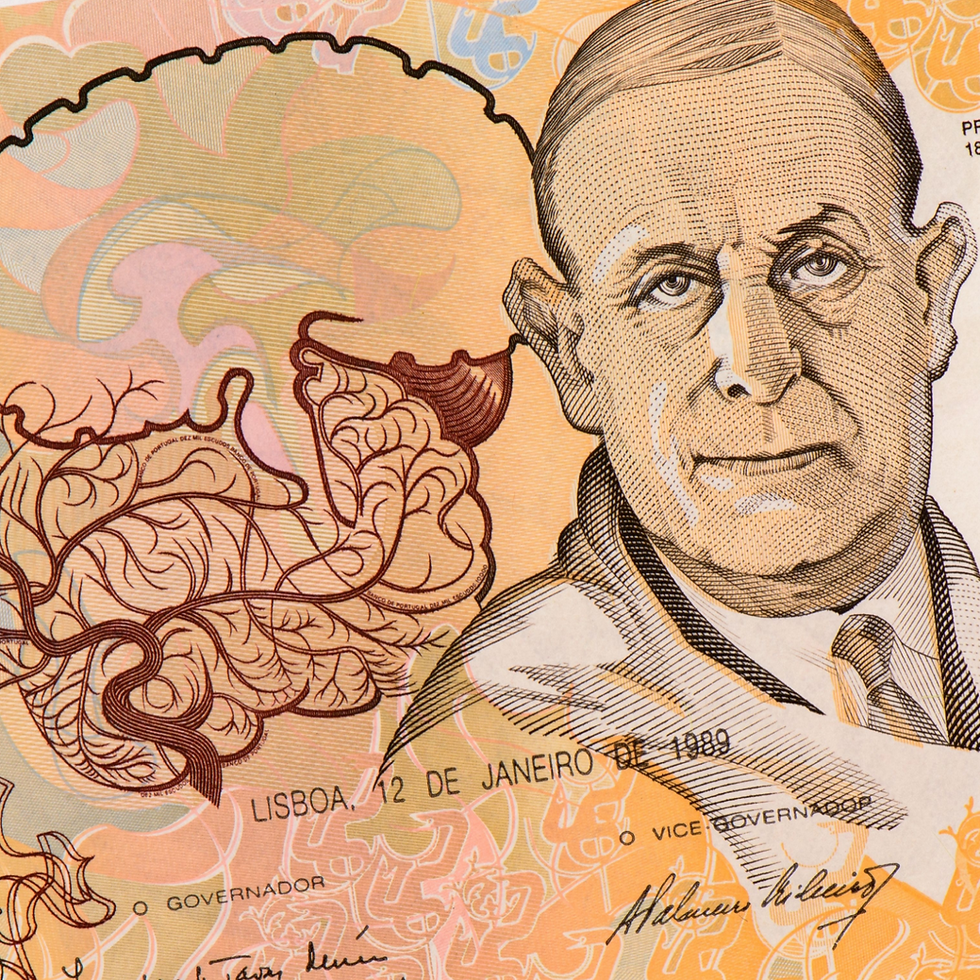

The modern lobotomy was introduced in the 1930s by Portuguese neurologist and politician António Egas Moniz. The procedure was eventually termed the "prefrontal leucotomy" as it was designed to obliterate the white matter tracts of the frontal lobe. Moniz theorized that mental illness resulted from maladaptive neural circuits and that severing connections in the frontal lobes could relieve psychiatric disease. Early reports appeared promising: patients often became calmer, less distressed, and less disruptive.

In 1949, Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work, a decision that remains controversial for obvious reasons. At the time, however, psychiatric institutions were overcrowded, effective treatments were scarce, and desperation shaped this peculiar innovation. Lobotomy offered something intoxicating to clinicians and administrators alike: speed, simplicity, and control. What it also offered was silence.

In the United States, the lobotomy was aggressively popularized by neurologist Walter Freeman, whose transorbital technique—often called the “ice-pick lobotomy”—allowed the procedure to be performed rapidly and without an operating theater. Thousands of patients underwent the surgery, frequently without meaningful informed consent, and often under local anesthesia.

The desired effect was often achieved: agitation diminished; emotional volatility softened; resistance faded. Yet these changes came at a profound cost. Patients often lost initiative, emotional depth, social judgment, and the ability to live independently. What was celebrated as therapeutic improvement frequently amounted to emotional flattening and cognitive diminishment. The procedure did not restore health; it suppressed expression. This ultimately raises a fundamental ethical question: Was lobotomy treating illness, or was it eliminating inconvenience?

Erasing Dreams

One of the most haunting consequences of the lobotomy involved something deeply human: dreaming. According to neuroscientists Mark Solms and Oliver Turnbull, frontal lobe damage, whether from injury or leucotomy, frequently resulted in the complete cessation of dreams (Solms & Turnbull, 2003). More disturbingly, some clinicians regarded the absence of dreams as evidence that the procedure had been successful.

Solms and Turnbull observed that dreaming shares key neural features with psychosis, describing dreams as “the insanity of the normal man.” From this perspective, eliminating dreams was interpreted as eliminating pathology, which really should give one pause. Dreams are not merely noise; they are expressions of emotional integration, memory consolidation, and subjective experience. Their disappearance signals not recovery, but the silencing of the inner world. When a medical intervention defines success as the eradication of inner life, something has gone profoundly wrong.

Phineas Gage: A Lobotomy Before it was Cool

Long before lobotomy entered clinical practice, the case of Phineas Gage offered an accidental preview of its effects. As a railroad foreman, Gage was an upstanding member of his community, and was a shrewd, smart businessman. Then in 1848, Gage survived a catastrophic railroad accident in which an iron tamping rod passed through his frontal lobe. On the construction site, dynamite failed to ignite, so he went over to investigate. Using his tamping rod, he poked at the dynamite causing it to explode, sending the rod careening through his skull, destroying his left eye, and taking out a significant portion of his frontal lobe. Thankfully, the rod was so hot from the explosion that it cauterized blood vessels, preventing him from hemorrhaging out. Gage got up right away and miraculously survived; though, he was heavily impacted by the injury.

Gage's recovery was quite complex, and he did eventually return to a functioning state through neuroplastic changes and adaptation. Gage retained basic intelligence and memory, yet his personality, impulse control, and social behavior were transformed (Kean, 2014). He became unreliable, emotionally volatile, and socially inappropriate.

In a rather amazing note from his physician Dr. Harlow, he writes that Gage is "fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible.” In other words, Gage turned into an impulsive jerk.

The case of Phineas Gage demonstrated to the entire scientific community that damage to the frontal lobe does not simply impair cognition, but it alters the self. Years later, the lobotomy would institutionalize this critical lesson, resulting in a dark period of medical history that impacted tens of thousands of patients.

Women, Control, and the Case of Rosemary Kennedy

The lobotomy was not applied evenly across populations. Women were disproportionately subjected to the procedure, often for behaviors perceived as disruptive rather than dangerous. Perhaps a man's wife wasn't cleaning up around the house; or perhaps a woman was 'acting out.' One the most well-known cases was that of Rosemary Kennedy, sister of President John F. Kennedy.

In 1941, fearing that her mood swings and independence might embarrass the family or (God forbid!) lead to pregnancy, her father authorized a lobotomy. The result was catastrophic. Rosemary was left with severe cognitive and physical impairments and spent the rest of her life institutionalized, unable to speak or walk.

Rosemary's story illustrates how the lobotomy often functioned less as medical care and more as social containment, particularly for women whose behavior challenged norms of obedience or propriety.

The Enduring Lesson: Humility as a Medical Imperative

The lobotomy eventually fell out of favor with the advent of psychopharmacology and growing ethical scrutiny, but its legacy remains deeply relevant. History repeatedly shows that medicine is vulnerable to treatments hailed as universal cures—especially when they promise efficiency and control over complexity.

The central lesson of the lobotomy is not merely that it failed, but why it failed. A procedure that destroys personality, imagination, and agency cannot be justified by reduced distress alone. Silence is not healing. Compliance is not wellness. When medicine mistakes suppression for cure, the consequences can lead to irreversible destruction.

The dark and fascinating history of the lobotomy reminds us that progress without humility is perilous. Treatments must be grounded not only in scientific rigor, but in ethical restraint and respect for the irreducible complexity of the human mind. When an intervention promises to solve everything, especially at the cost of identity, we should pause, question, and remember this history.

Another important lesson that we should all take seriously is that sometimes physicians violate their Hippocratic Oath and ultimately harm their patients. Many treatments and interventions that are being conducted today in the name of science and progress will be looked upon with shock and horror in the future—the same way we now regard the horrifying history of lobotomies.

References

Kean, S. (2014, May 7). The true story of Phineas Gage is much more fascinating than the mythical textbook accounts. Slate Magazine.

Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. (2003). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. Karnac.

Comments